No matter how low you think you can go, someone is always willing to go lower...

It can be very tempting to want to use price discounting to increase sales. It’s an obvious lever to pull, but it’s also a very dangerous one. Here are 18 reasons why you should never compete on price…

Low price comes from economies of scale and systems, not your ass

Price advantage comes from economics. E.g., a larger company has access to bulk discounts from suppliers, lower interest rates; can invest in machines and automation, etc. A larger company can also reuse investments and amortize costs (E.g., car makers using the same engine or chassis in different cars; spreading the development costs across all their models).

Price advantage can also come from having systems that efficiently and reliably 1) provide continuing value and 2) extract wealth from customers. E.g., Amazon’s Kindle increases sales from Amazon’s online store. Because of this, Amazon can justify sacrificing profits on the Kindle (to support a low price), since the increased revenue from the back-end systems over the entire lifetime of each Kindle user makes up for it. Any business trying to compete with the Kindle (or iPad) without a similar way to generate income after the initial sale of the device is at a serious economic disadvantage.

Businesses with reliable systems (and deep pockets) are also able to delay profits for much longer, knowing that they will see the profit at a later time. E.g., they could run campaigns that sink hundreds of thousands of dollars negative in the initial months before they even see a cent of profit (Proactiv).

Without these advantages, your low price is not supported by economics and therefore unsustainable — it can very easily be crushed by a business with a true economic advantage. E.g., Walmart coming to town… or outsourcing.

Price is an unsustainable advantage for any business of any size. (I challenge you to name one business that has successfully maintained their lowest-price advantage. Every lowest-price option you see today has been preceded by another business that used to be the lowest-price option.)

People who shop only by price are loyal only to price

There are two kinds of people who shop only by price: those who have no choice (they spend all their income on necessities and cannot afford anything but the cheapest option); and those who choose to be frugal in a particular area in their life. In both cases, the moment a cheaper option appears, they will stop buying from you.

There is no value in being “2nd-cheapest”

When a lower-price alternative appears, the price shoppers and deal hunters will leave you cold and bone dry, as they swarm to the cheaper option. (If they only care about price, why go for 2nd-cheapest when they can go for cheapest? Why buy from you if someone else offers them a deeper discount?) It’s an extremely unstable advantage to maintain. Further, the cost of failure of a low-price positioning is tremendous — when the entire business is built for low price, it’s often inept at competing any other way. The saying is:

“Live by price, die by price.”

People who spend a significant chunk of their income on necessities are very sensitive to the economy

Most people spend a portion of their earned income on necessities and a portion on non-necessities (say 50% on necessities and 50% on discretionary spending). These are very volatile customers, because the moment a shadow of doubt is cast on the economy, or when times are hard, they can tighten up their purse strings and instantly stop spending on non-necessities and save instead… or switch to cheaper options (generic instead of brand name). This can cause what used to be a raging river of customers to shrivel up to a trickle, and businesses positioned here are often the ones you see getting slaughtered during recessions.

Low prices attract the wrong people and bad customers

Deal hunters. bottom-feeders. Like vultures swooping around for a carcass to pick on, or a lonely drunk looking for an easy one-night-stand half an hour before closing… they don’t particularly have a preference. They buy only because of the low price, but are not interested in any sort of relationship, never convert to more valuable customers and have no intention of returning.

Attracting people with price discounts trains bad behavior

When you rely on price discounts to bring people into the door, it trains and conditions people to respond to price discounts. The more you do this, the more you corrupt your price integrity, and the more you encourage your customers to anticipate discounts… until the only thing they will respond to are discounts — suppressing your price forever.

It’s a very bad economic trade-off

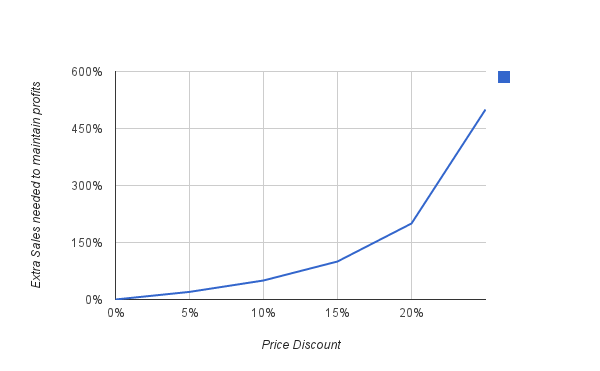

Yes, by lowering the price, more people may buy. But at a lower price, you also get a lower profits. So you ought to wonder, how many extra sales would you need at the lower price to outperform the original price? You force me to bust out the charts:

Let's say your profit margin is 30%. This shows how many extra sales you need to get the same amount of profit, when you lower your price. E.g., If you lower your price by just 15%, you have to make 100% more sales (2x). A concrete example: say each unit is sold at $100, costs $70 and profit per unit is $30. If you sell 10 units, profit is $30 x 10 = $300. With a 15% discount, each unit is sold at $85. Cost is still $70, so profit per unit becomes $15. To get the same $300 profit, you need to double sales from 10 to 20: $15 x 20 = $300. So if you have a 30% profit margin and you plan to offer a 15% discount, you need TWICE as many sales. If your 15% discount doesn't double your sales, you're just being silly.

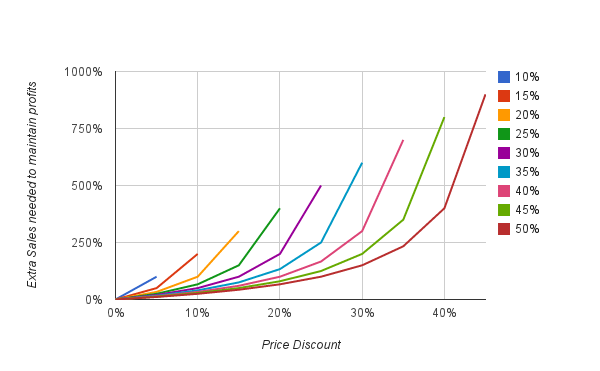

It’s an even worse trade-off if your margins are slim

This shows how many extra sales you need when you lower your price (at various profit margins). The slimmer your profit margins, the far greater quantities you have to sell to bring home the same amount of profits as the undiscounted price. E.g., using the same scenario of offering a 15% discount: if your margin is 20% instead of 30%, you'd have to make 300% more sales (4x).

The lower your price, the larger your numbers must be (and the more complicated things get)

As shown above, the number of sales required to make a profit goes up exponentially as you lower your price. This often means you have to deal in larger volumes, and this increases the complexity. Large volumes require better infrastructure (and more investment) to serve them. A business that only requires 1-10 customers a month to be profitable (e.g., high ticket, high margins) can operate in a fairly low-tech manner. For example, supercar manufacturer Pagani Automobili has always been profitable, even though it has only built 130 cars in the past 10 years, with fewer than 50 employees. It sold just 15 cars in 2010 for a revenue of about $20 million. Their latest car, the Huayra, sells for over $1 million each. In contrast, a business that must serve 10,000 customers a month (because of low margins) requires a substantial amount of infrastructure, automation and/or employees.

If you need large numbers to be profitable, it’s a sign you have a poor system or process for extracting wealth

Nothing can fix bad economics. I.e., if your system for making money is bad, nothing can save you. That being said, it is common for businesses to not do enough to maximize the lifetime value of a customer.

E.g., say someone walks into a clothing store to buy a suit for an interview. Although he came in for a suit, there’s a good chance he may also want a tie, shirt, undershirt, shoes, socks, and maybe even a watch. Knowing that a percentage of people who buy suits for interviews do actually get the job, the business can entice the customer to return to buy work clothes, and maybe something casual for his celebratory vacation before he starts working. That very same customer may have friends who are also job-hunting (and can be leveraged to orchestrate referrals). Later, if he acquires better taste (or a girlfriend), he may want his suit, shirts or pants tailored… and so on. Now if the business owner only cared about selling one suit, he’s doing a poor job of serving his customers (and extracting wealth), and he’s leaving plenty of money on the table.

Having to compete on price is a sign of 2 serious problems:

- You have not found your ideal clients (or they are unreachable)

You may be reaching people who don’t have an urgent desire or need for what you offer. E.g., selling burgers to people who want pizza. - There is no demand for your solution

E.g., selling hamburgers when no one eats meat. This is a common problem when business owners create something they want, instead of listening to what their ideal clients want, and then creating something for them.

With low prices, your customers are worth little, and you can’t afford to take care of them well

You can’t hire the best people, you can’t afford to offer them the best service, you don’t have time to give attention to each person, you can’t afford to spend money to attract your most valuable customers, you have to skimp on quality, etc.

Nothing you do can change the belief that “Low price = low quality”

People equate price with quality (and low price with low quality). But it’s not just perceived quality that’s degraded by low price — actual quality (and actual efficacy) is damaged too. People believe that they “get what they pay for” so much that it affects reality.[1]

People who pay more are happier and get better results

People rate the same wine as tasting better when they are told it is more expensive.[2] Athletes taking the same sports drink perform better when they are told that their drink was more expensive.

Similarly, people who pay less get worse results

People given the same pain reliever feel more pain when they are told that the pills they have taken are discounted.[3] People who consumed a price-discounted energy drink (claiming to boost mental acuity) performed worse at solving puzzles than the people who consumed the same drink at regular price.[4]

There are people who are happy to pay more

There are people who can afford to and want to spend more. You should not impose your values on them. If you don’t serve them, someone else will.

People don’t reliably know what they like, and can’t reliably decide how much something is worth

Contrary to what is widely taught in Economics, Psychology reveals that value is arbitrary. Value (and price) is derived from external cues, and these cues can be arbitrary (and even unrelated to the item being evaluated). Research by Ariely et al. showed that how much someone is willing to pay for a bottle of wine or even computer peripherals can be influenced by something as arbitrary as the last 2 digits of their social security number.[5] [6]

If you think price is your only competitive advantage, you are not fully leveraging all your assets

Consider the other things people are willing to pay for, such as: convenience, speed, personal service, good manners, something in common with you, good customer support, ease-of-use, guarantees, included education/how-to/recipes, an experience to remember, positive energy, proof that it works, comfort, trust, celebrity endorsement, status, community, respect, nostalgia, … and so much more. Price should be the last option on your list, after you have extracted every ounce of value from your other assets.

Alright, my neck is killing me so I’ll have to stop here. That’s all I have for now. Hopefully I’ve given you enough to chew on, and a glimpse of why you must never compete on price. The only direction your prices ought to move is up.

Add your comment: